When Asking A Question, How Does A Person's Voice Change?

This Article From Issue

September-October 2016

Book 104, Number 5

Vocal signals amid animals can carry unlike types of messages simultaneously. The husky of a frog or the screech of a monkey conveys information virtually the animal making the sounds: its motivation, its power to defend resources, its health, and even its genetic quality. Other animals have evolved to pay attention to this implicit information and adjust their own beliefs accordingly, considering doing then can increment their ain evolutionary fitness.

For example, enquiry past two of us (Anderson and Nowicki) shows that in an aggressive encounter between songbirds, the loudness of a bird's song reliably signals the likelihood that the bird will physically attack its opponent. Both the signaler and the recipient stand to benefit from the data exchange, because both can avoid a potentially plush fight if they are not equally motivated or able to defend whatever is being contested, such as a territory, a prospective mate, or a source of food.

Speech is unique to humans, and it is far more complex than the communication systems of animals such as songbirds, but we too are influenced by nonverbal aspects of speech. The idea that listeners are afflicted not just by the words we say, merely also by how we say them, should come as no surprise: We all can call up of instances in which the same words said with different inflections can hateful very dissimilar things. What is more than surprising is that subtle characteristics of speech communication—features of which we are inappreciably aware—can have a significant affect on our perceptions of a person, fifty-fifty in contexts where we might think these perceptions should exist irrelevant. Our research explores one such context that is particularly topical in this 2016 ballot season: how song traits, specifically voice pitch, can influence our selection of leaders.

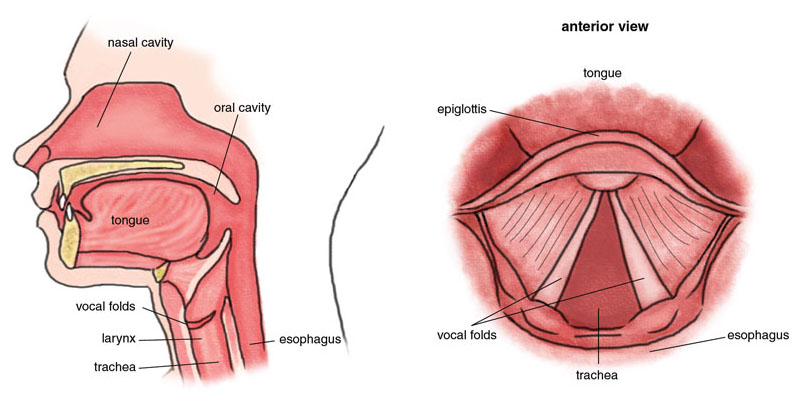

Vocalism pitch, the perceived "highness" or "lowness" of a voice, fundamentally is an expression of physiology, not psychology. All sounds are the event of minute fluctuations in air force per unit area; voice communication sounds in item stand for patterned fluctuations that are created when we force air through the vocal tract. The flow of air is modified past the vibration of the song folds (or vocal cords) in our larynx (or vocalization box), as well as by the movement and relative positions of our natural language, jaw, lips, and so forth. The specific pitch of a person's voice reflects the central frequency at which the song folds are vibrating and thereby imposing periodic variations in air pressure, measured in hertz, or cycles per second.

As with the strings of a guitar or piano, when vocal folds are longer and thicker, they tend to vibrate more slowly and so produce a lower-pitched voice, whereas shorter and thinner vocal folds vibrate more quickly and thus produce a higher-pitched voice. The size of the vocal folds is largely determined by the size of the larynx, and their thickness is further influenced past the action of hormones such as testosterone. The larger the larynx, the longer and thicker the song folds and the lower the pitch of the voice. Typical male voices range in pitch from 85 hertz to 180 hertz; typical female voices, from 165 hertz to 255 hertz. The considerable difference in vox pitch between men and women reflects not only the average difference in body size betwixt the sexes, merely also the fact that the size of the larynx is a secondary sexual characteristic partly controlled by testosterone; this is why the male person larynx—usually referred to as the "Adam's apple"—enlarges disproportionately with the onset of puberty.

Although vox pitch is mostly determined past throat anatomy, a speaker can modulate the pitch of his or her voice. A well-known historical example, highlighted in the 2011 motion film The Iron Lady, is the modulation in pitch of Margaret Thatcher'south voice that resulted from the vocal training she underwent before she became prime number minister of the United Kingdom. Her biographer, Charles Moore, has suggested that learning how to attune the pitch of her voice may have helped Thatcher advance her political career. This kind of training can alter voice pitch but then far, however, within the constraints of the speaker's anatomy and physiology. To take an example from a different realm of life, even with extensive vocal training some low-voiced women cannot develop the ability to sing in the soprano musical range, and non all men have the physical ability to sing a bass role. A person can conform the pitch of his or her speaking vox to some degree, but in most cases the alter is pocket-size in comparison with the innate differences of pitch amidst individuals.

Using recorded voices that take been manipulated to sound college or lower, psychologists and linguists have demonstrated that a person's voice pitch affects how others perceive her or him. Almost of this inquiry is based on experiments in which participants are presented with a forced-selection task, existence asked to select which manipulated phonation—the higher or the lower i—is more bonny, stronger, younger, or more salient by some other benchmark, depending on the question being studied. A benefit of this research pattern is that the field of study is making his or her judgment based solely on voice pitch; the two recordings that the subject is judging are otherwise identical, spoken by the same person and differing simply in pitch.

Experiments of this kind reveal a number of important ways in which voice pitch influences how we perceive and collaborate with 1 another. For example, males with lower-pitched voices tend to be perceived as more attractive, physically stronger, and more "ascendant" (a term offered by the experimenter to mean, loosely, "respected," "commanding," "more than likely to be followed," or something along those lines). For females, the standard is dichotomous: Women with higher-pitched voices tend to be considered more attractive, whereas those with lower-pitched voices are perceived every bit more than dominant.

It's possible that these perceptions may have evolutionary underpinnings. For example, research by Gregory Bryant and Martie Haselton at the University of California, Los Angeles, shows that hormonal changes cause the pitch of a woman'south voice to rise during the point in her menstrual wheel when she is most likely to conceive. In an evolutionary sense, then, women with higher voices should be perceived as more attractive, because a high vocalisation is associated with elevation fertility on average. Past dissimilarity, lower voices in men tend to correlate with higher levels of circulating testosterone in the claret stream, which in plough correlates on average with increased concrete and social aggressiveness, as shown in studies by John Archer at the University of Fundamental Lancashire and David Puts at Pennsylvania State University, amongst others. One might well suppose that at some early indicate in man evolution, females perceived these qualities positively considering they indicated health, good genetics, and the physical power to defend a mate and offspring from threats.

Research subjects, both male and female person, preferred a lower-pitched vocalism, whether the candidate was female or male.

The unmistakable influence of voice pitch on our perception of a speaker suggests that this trait may play a role not just in social interactions but too in how we perceive and select our political leaders. The start study to exam this proposition, conducted by Cara Tigue and her colleagues at McMaster University, consisted of two experiments. In the first, recordings of spoken remarks by ix The states presidents were manipulated digitally to yield college- and lower-pitched versions of the original. A total of 125 research subjects (61 women and 64 men) were asked to "vote" for the higher- or lower-pitched version of each of the nine pairs. On average, the subjects voted for the lower-pitched voices 67 percent of the time. In a 2d experiment, Tigue and colleagues manipulated six novel male voices rather than those of known leaders. The forty subjects (20 women and xx men) were again presented with pairs of voices and asked to vote for either the higher- or lower-pitched phonation of each pair. Equally in the presidential voices experiment, the subjects preferred candidates with lower-pitched voices; this time the candidates with lower voices were selected 69 percent of the time.

Our own interest in the influence of voice pitch on the selection of leaders represents the coming together bespeak of 2 lines of investigation that might otherwise seem to accept zilch in common: song signaling, peculiarly in birds (Anderson and Nowicki), and political behavior (Klofstad). At the same fourth dimension that Tigue and colleagues were conducting their written report, nosotros carried out a like forced-choice experiment. Nosotros start recorded a number of men and women proverb, "I urge you to vote for me this November," a nonpartisan but politically relevant phrase. Nosotros then altered those voices digitally, both to slightly raise and to slightly lower the pitch of each. The resulting gap between the college- and lower-pitched version of each manipulated voice is equivalent to approximately 40 hertz (on a piano, roughly the difference between A3 and C4, or heart C).

female–loftier / female–low / male–high / male person–low

Non simply did subjects hear only a nonpartisan argument request for back up, simply they also received no information as to the leadership role beingness sought. More specifically, to rule out the possibility that the influence of voice pitch might differ depending on the political office at pale, we did non tell the participants whether they were being asked to vote for a member of Congress, the president of a parent teacher organization (PTO), or any other item position. Nosotros presented subjects with multiple pairs of manipulated voices (10 male and 17 female) and asked which phonation they would choose from each pair. When we calculated the proportion of votes cast past each bailiwick for the lower voice of each pair, we found that both male and female voters preferred a lower-pitched voice, whether the candidate was male or female; the proportion of votes cast for candidates with lower voices was roughly 60 percent regardless of the sex activity of either the candidate or the voter.

to a higher place): In an experiment that two of the authors (Klofstad and Anderson) conducted with Susan Peters at Duke University, subjects were more likely to vote for candidates whose voices were roughly 40 hertz deeper than those of their opponents.">

to a higher place): In an experiment that two of the authors (Klofstad and Anderson) conducted with Susan Peters at Duke University, subjects were more likely to vote for candidates whose voices were roughly 40 hertz deeper than those of their opponents."> The consistency of our results with those of Tigue'south study led us to ask, Why practise voters adopt leaders with lower-pitched voices? To begin to answer this question, we conducted another experiment, in which we once more asked participants to choose between candidates with lower- or higher-pitched voices, but this fourth dimension nosotros simultaneously asked which voice of each pair they perceived as sounding stronger, more than competent, and older.

Information technology makes sense to inquire about perceptions of strength and competence—these are undoubtedly desirable qualities in a leader—but the question about age may need more explanation. We reasoned that one logical reason for the finding that voters adopt leaders with lower voices is that these candidates are perceived every bit older, and thus wiser and more experienced. There may be some merit to this notion, given that other research has shown that age can be predicted accurately based on various characteristics of a person's vocalism, including pitch. Research conducted across 26 countries on 6 continents—including Argentina, Australia, France, Japan, Uganda, and the Usa—by Corinna Löckenhoff of Cornell University and her colleagues shows that older individuals generally are perceived as wiser than younger individuals. Moreover, research by Joann One thousand. Montepare of Lasell College in Massachusetts and her colleagues shows that speakers with older-sounding voices are perceived as wiser than those with younger-sounding voices. Consequently, we wondered whether the influence of voice pitch on voters' preferences could be influenced by perceptions of historic period.

During our follow-up experiment, in which nosotros asked subjects to choose among candidates also equally to rate them, on the basis of their voices, according to their credible competence, strength, and age, we constitute that each of these three perceptions tin explain some of the preference for candidates with lower voices. Still, contrary to our prediction that the preference for lower-voiced leaders is driven primarily past a perception that they are older, our results suggested that we prefer leaders with lower voices largely considering nosotros run into them as stronger and more competent; only secondarily do we prefer to vote for them because nosotros perceive them as older and more experienced. Our perceptual biases for vocal behavior, then, appear to have less to exercise with attributes such as wisdom or feel than we might consciously hope for in a politician.

The growing number of experimental studies on the influence of phonation pitch on the selection of leaders leads to the obvious question, Are voters in real elections actually influenced by the pitch of a candidate's voice? We now have information suggesting that they are. A study conducted by ane of us (Klofstad) of all 435 U.S. House elections in 2012 showed that vocalization pitch correlated with balloter outcomes: Both male and female candidates with lower voices were significantly more than probable to win. For instance, candidates who had a lower voice than their opponents were 13 per centum more than likely to win office and garnered an average of four per centum more of the vote share. These results held up even when a multitude of alternative explanations for balloter outcomes were deemed for in the assay: campaign spending, incumbency, the candidate's sex, and the ideological preferences of voters in the candidate's congressional district. Information technology is important to note that these data (unlike information from our other studies) are observational, not experimental, and thus we cannot say that candidate voice pitch "caused" a House candidate to win or lose in 2012. At the very least, all the same, these results conduct with our experimental findings by showing a potent and statistically pregnant correlation betwixt having a lower vocalism and balloter success.

On further assay, results from the 2012 U.Southward. Business firm elections revealed some interesting wrinkles in the overall design of preference for candidates with lower-pitched voices. First, the preference is not consistent once the sex of the candidates running against each other is taken into account. We establish that when the pitch of a male candidate's voice was forty hertz lower than that of his male person opponent'south (the gap we used in the forced-choice studies described earlier), that difference was associated with a 13.9-percent higher likelihood of that candidate's defeating a male opponent. When a male person candidate was running against a female candidate, all the same, having a voice 40 hertz lower in pitch decreased his likelihood of winning past 25.8 percentage points. In other words, our observational data propose that the reward given to lower-pitched male voices in a male-male contest appears to piece of work in the opposite management in a male person-female contest.

The caption for this double-edged outcome is not still clear. Could information technology be that male candidates with lower voices are perceived every bit too aggressive when paired confronting a female opponent? Testing such a hypothesis will crave experimental studies in which male and female candidates with differently pitched voices compete confronting each other, and in which the research participants are asked not merely to choose one candidate but likewise to written report their perception of each candidate'south aggressiveness. We hope to conduct such a exam in the nigh future.

A second complication in the blueprint of preference for lower-pitched voices has to practice with the type of leadership position being sought. Apropos of the sexual activity differences described higher up, two of united states (Anderson and Klofstad) hypothesized that voters' preference would shift to college-pitched (that is, more feminine) voices if the race in question was for a leadership position that is typically held past women. To examination this idea, we replicated our forced-choice experiment with higher-pitched and lower-pitched voices of candidates, just this fourth dimension we asked 1 fix of participants to vote for a member of the schoolhouse board (a municipal-level governing trunk that oversees schools) and some other ready to vote for president of the PTO (a schoolhouse-level voluntary service arrangement). Both positions are concerned with the welfare of children; in the United States, where our study was conducted, women are more likely than men to concur both types of positions.

In contrast to our prediction that college-pitched voices would win out in elections for more conventionally feminine leadership roles, we found that both men and women voters preferred female candidates with deeper voices for both the school board and the PTO presidency. When both of the candidates were men, however, the participants in our experiment reacted differently: Men preferred men with lower-pitched voices for both positions, but women did not discriminate between higher- and lower-pitched male voices when voting for either leadership position. These results suggest that the influence of voice pitch on perceptions of leadership capacity is largely consistent across unlike domains of leadership; at the aforementioned time, the results allow for the possibility that when it comes to traditionally feminine leadership roles, women may take more than clashing attitudes well-nigh male voices than men do.

In this same vein, more than detailed analysis of our previous forced-choice experiments revealed that the sexual activity of the candidate and the sexual activity of the voter both matter. The full general pattern is that voters prefer leaders with lower voices regardless of the sex of the candidate or that of the voter. However, this bias is stronger amongst female voters, particularly when they are judging female candidates. That is, women accept a especially stiff preference for deeper-voiced—and thus, presumably, stronger and more than dominant-sounding—female leaders. An culling interpretation of this result rests on the finding from numerous studies—including those by Joan Y. Chiao, director of the International Cultural Neuroscience Consortium, and her colleagues, and past Kyle Mattes of Florida International University and Caitlin Milazzo of the Academy of Nottingham—that candidate bewitchery can affect elections: A female candidate with a deeper voice (a trait conventionally considered to exist less feminine and thus less attractive) may fail to benefit from the generic preference for lower-pitched voices, at least among male person voters.

Does the linguistic communication-processing circuitry of the man brain bargain with meaning autonomously from intonation?

Moreover, experimental studies that one of usa (Klofstad) conducted with our colleagues Lasse Laustsen and Michael Bang Petersen at Aarhus Academy take also shown that the preference for leaders with lower-pitched voices tin can vary with the political views of the voter. This serial of forced-choice experiments amidst Americans revealed that when the candidates are men, the bias in favor of leaders with lower voices is stronger among Republicans and self-described conservatives than among Democrats and self-described liberals. For example, in 1 of these experiments, 242 participants who were registered to vote as Republicans preferred male candidates with lower voices 63 percent of the time, whereas 289 registered Democrats preferred male candidates with lower voices but 54 percent of the time, a statistically significant difference.

This bias falls in line with the results of research by John Duckitt and Chris G. Sibley of the University of Auckland, and by John Hibbing of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and his colleagues, among others, showing that Republicans and conservatives are more likely to view the world as a competitive and dangerous identify than are Democrats and liberals. Because people with lower-pitched voices tend to have higher testosterone levels, and because individuals with more testosterone are more aggressive both physically and socially (as shown by Archer and Puts, among others), information technology perhaps makes sense that right-leaning individuals bear witness a more marked preference for leaders with lower voices than do their left-leaning fellow citizens.

Our studies and those of others show that, all other things being equal, vocalization pitch tin affect our pick of leaders. But in real elections, all other things are never really equal. For instance, we've already shown that an upshot of vox pitch can be reversed when men are competing with women rather than with other men. Futurity tests might examine whether this result is specifically based on the gender pairing or can be attributed to other confounding furnishings. Another group of studies could explore how physical appearance—including height and weight, race, facial appearance, and many other traits—influences electability; more realistic experiments could present candidate voices and faces in tandem, to compare the effects of visual and vocal stimuli.

We have established that a speaker's vox pitch tin significantly affect listeners' impressions of him or her, although many specific questions remain about how this influence works in diverse contexts. Meanwhile, another line of investigation awaits: an examination of how the listeners' perceptions of pitch are themselves influenced past the content of a oral communication. Does the language-processing circuitry of the human brain deal with pregnant apart from intonation? Existing research suggests that this could be the case. For example, studies by Anthony Niggling of the University of Stirling and his colleagues, and by Brian Spisak at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and his colleagues, among others, have shown that leaders with more "masculine" faces (that is, faces that are wider in face up and nose, with thinner lips and with larger and more than angular jaws) are preferred in times of war. With these results in mind, we plan on designing experiments to exam whether the preference for leaders with lower-pitched voices is stronger when the candidate speaks almost foreign rather than domestic policy.

In this same vein, we are interested in whether candidates vary their voice pitch based on the audience they are addressing. It is already known from the work of Puts and his colleagues that men vary their vocalism pitch based on their perceptions of their ain authorisation relative to the human they are speaking with. Likewise, in their report of presidential candidates, Stanford Gregory and Timothy Gallagher of Kent State University in Ohio argue that speakers shift their tone of phonation to more closely match the tone of the more than dominant speaker in the conversation. At present that information technology has been documented that speakers tend to attune their tone of voice based on whom they are speaking to, we plan to test whether speakers raise the pitch of their voice (that is, feminize information technology) when speaking to a female audience, and lower their voice pitch (and masculinize it) when speaking to a male audition.

Finally, a fundamental proffer remains untested: People with lower voices may have an edge in elections for positions of leadership, merely do people with lower voices actually brand amend leaders? On the one paw, if individuals with college testosterone levels (as demonstrated by their deeper voices) are more aggressive, both physically and socially, a leader with a lower vox might be a more forceful advocate on behalf of his or her constituents. On the other paw, given that political conflict in mod times arises from a disharmonism of complex ideologies at least every bit often as from contests of physical dominance, individuals with more testosterone and lower voices may exist overly aggressive and less adept at cooperation. Perhaps our predilection for certain voice characteristics did yield better leadership at some signal in our afar past, and it is possible that such predilections go along to serve us well in selecting expert leaders. Only it is too possible that an unconscious bias for lower voices causes u.s. to vote against our best interests in today's increasingly interdependent world.

In any event, information technology is articulate that even today this bias can take an impact on our decisions at the polls. Our perceptions of a leader's phonation are unlikely to override our opinions on policy, partisanship, and all the other influences on electoral outcomes. The crucial indicate, however, is that nowadays, when many elections are won past the narrowest of margins, it is conceivable that these thin, impressionistic judgments can and practise bear upon how nosotros choose our leaders, and and so nosotros would do well to exist aware of them.

- Anderson, R. C., and C. A. Klofstad. 2012. Preference for leaders with masculine voices holds in the example of feminine leadership roles. PLoS One vii:e51216.

- Borkowska, B., and B. Pawlowski. 2011. Female vocalisation frequency in the context of authorization and attractiveness perception. Creature Behaviour 82:55–59.

- Bryant, 1000. A., and Yard. Grand. Haselton. 2009. Vocal cues of ovulation in human females. Biology Letters 5:12–15.

-

- Feinberg D. R., B. C. Jones, A. C. Niggling, D. Yard. Burt, and D. I. Perrett. 2005. Manipulations of key and formant frequencies influence the attractiveness of human male person voices. Animal Behaviour 69:561–568.

- Gregory, S. W., and T. J. Gallagher. 2002. Spectral analysis of candidates' nonverbal vocal advice: Predicting U.S. presidential election outcomes. Social Psychology Quarterly 65:298–308.

- Jones, B. C., D. R. Feinberg, L. Chiliad. DeBruine, A. C. Piddling, and J. Vukovic. 2008. Integrating cues of social interest and voice pitch in men's preferences for women's voices. Biological science Letters 4:192–194.

- Klofstad, C. A. In press. Candidate phonation pitch influences election outcomes. Political Psychology .

- Klofstad, C.A., R. C. Anderson, and S. Nowicki. 2015. Perceptions of competence, strength, and age influence voters to select leaders with lower-pitched voices. PLoS One 10:e0133779.

- Klofstad, C. A., R. C. Anderson, and South. Peters. 2012. Sounds like a winner: Voice pitch influences perception of leadership chapters in both men and women. Proceedings of the Regal Society B: Biological Sciences 297:2698–2704.

- Laustsen, L, Grand. B. Petersen, and C. A. Klofstad. In press. Vote option, ideology, and social dominance orientation influence preferences for lower-pitched voices in political candidates. Evolutionary Psychology.

- Puts, D. A., C. R. Hodges, R. A. Cárdenas, and S. J. C. Gaulin. 2007. Men's voices as dominance signals: Vocal fundamental and formant frequencies influence authorization attributions among men. Development and Human being Beliefs 28:340–344.

- Tigue C. C., D. J. Borak, J. J. One thousand. O'Connor, C. Schandl, and D. R. Feinberg. 2012. Voice pitch influences voting behavior. Evolution and Human Behavior 33:210–216.

Source: https://www.americanscientist.org/article/how-voice-pitch-influences-our-choice-of-leaders

Posted by: peaseandided.blogspot.com

0 Response to "When Asking A Question, How Does A Person's Voice Change?"

Post a Comment